The Hours of Le Goux de La Berchère (Use of Paris)

, France, Paris, c. 1420

The Hours of Le Goux de La Berchère (Use of Paris)

Description

This is a ravishing manuscript in near-perfect condition produced in Paris at the time of the Bedford Master by his chief disciple The Master of the Munich Golden Legend. Its rich palette, sensitive attention to decorative detail, lavish use of gold (including some gold tooling), and creative style and iconography are typical of the earliest Parisian work of our master when he was most under the influence of the Bedford Master and before his Rouen period. The many roundels, enhancing the principal miniatures, are enchanting. Once in the collection of J.R. Ritman, it has for the past two decades been inaccessible in a private collection.

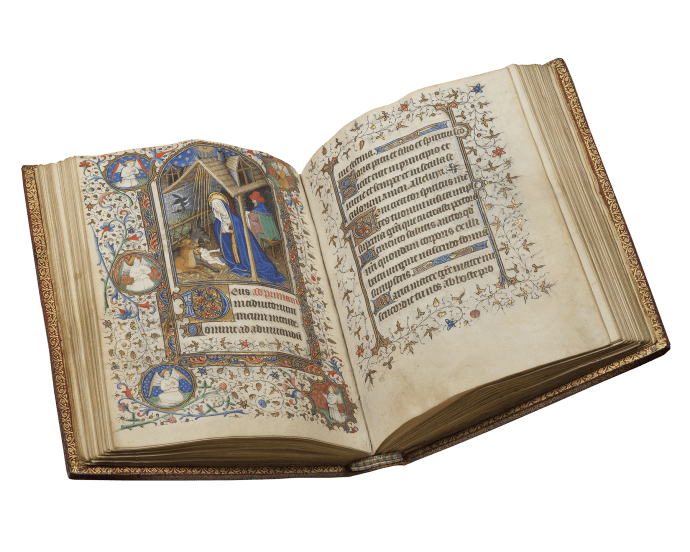

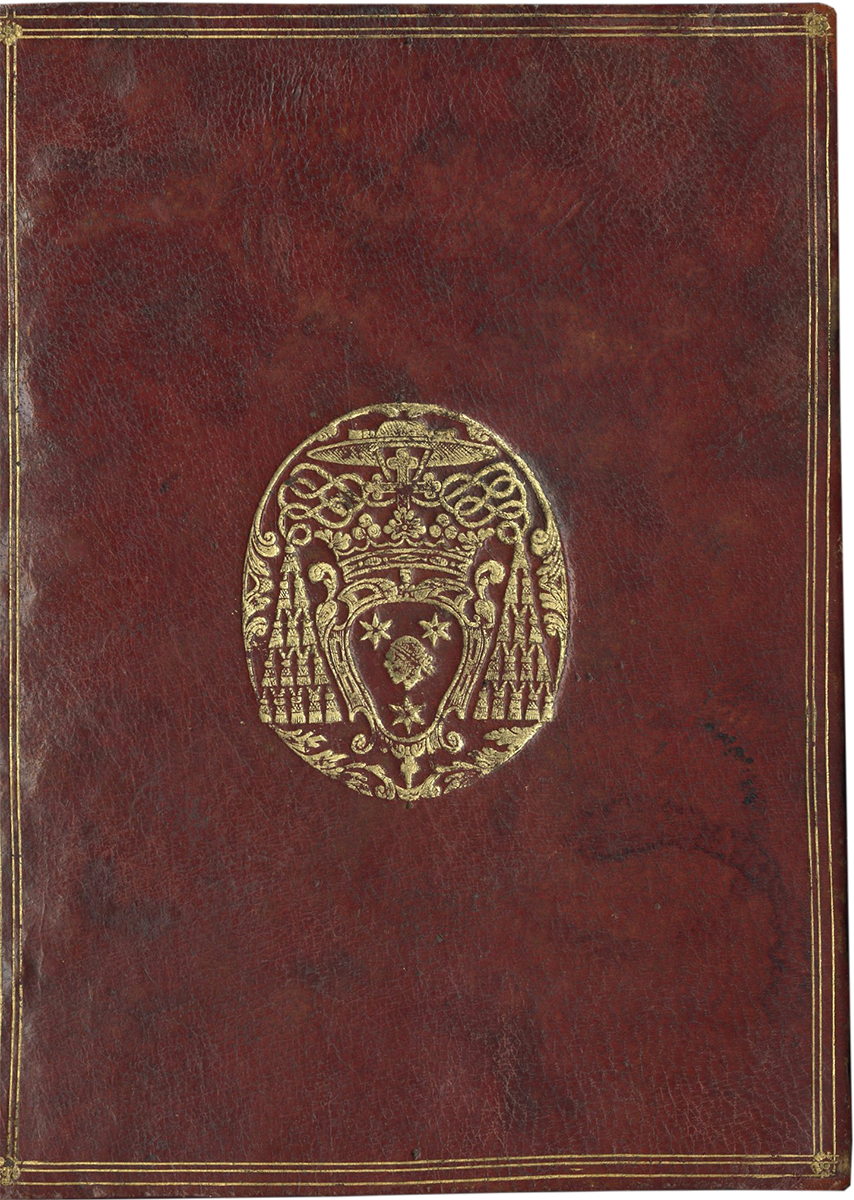

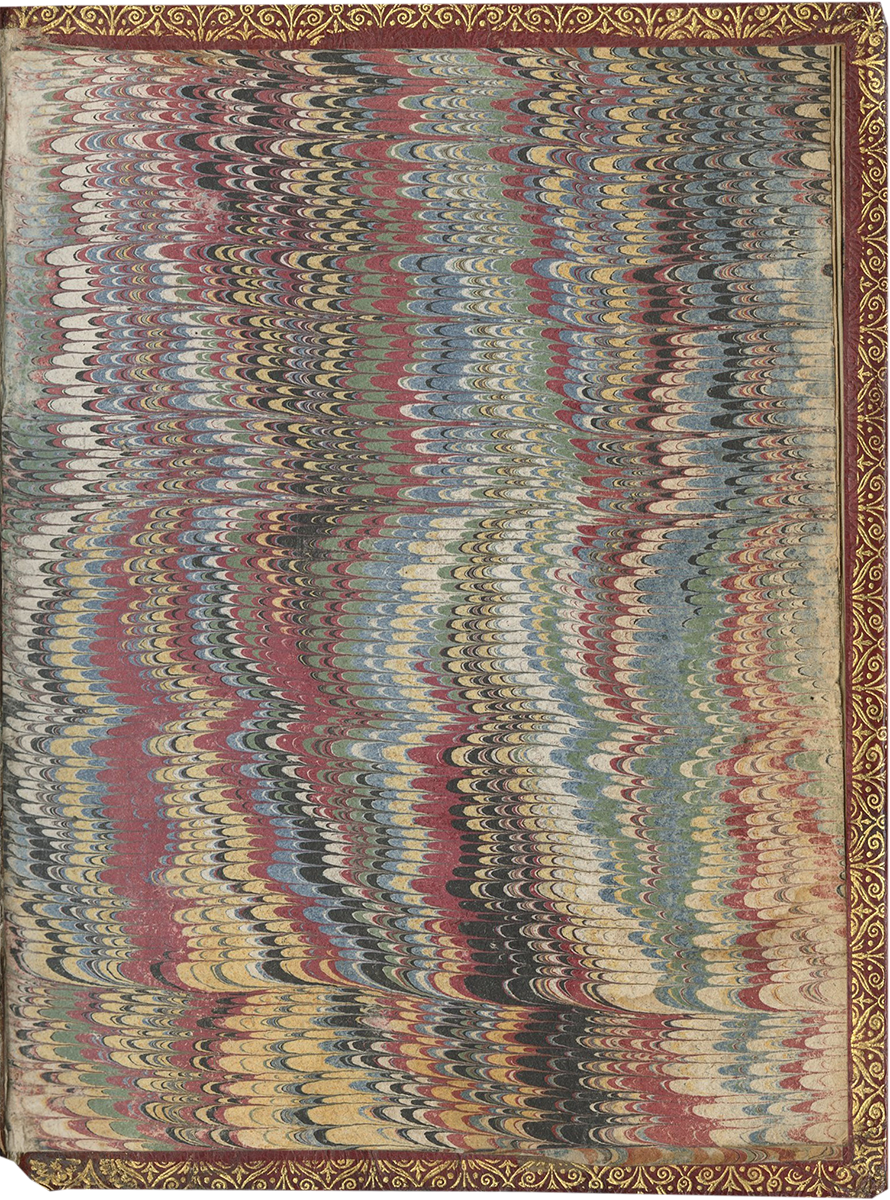

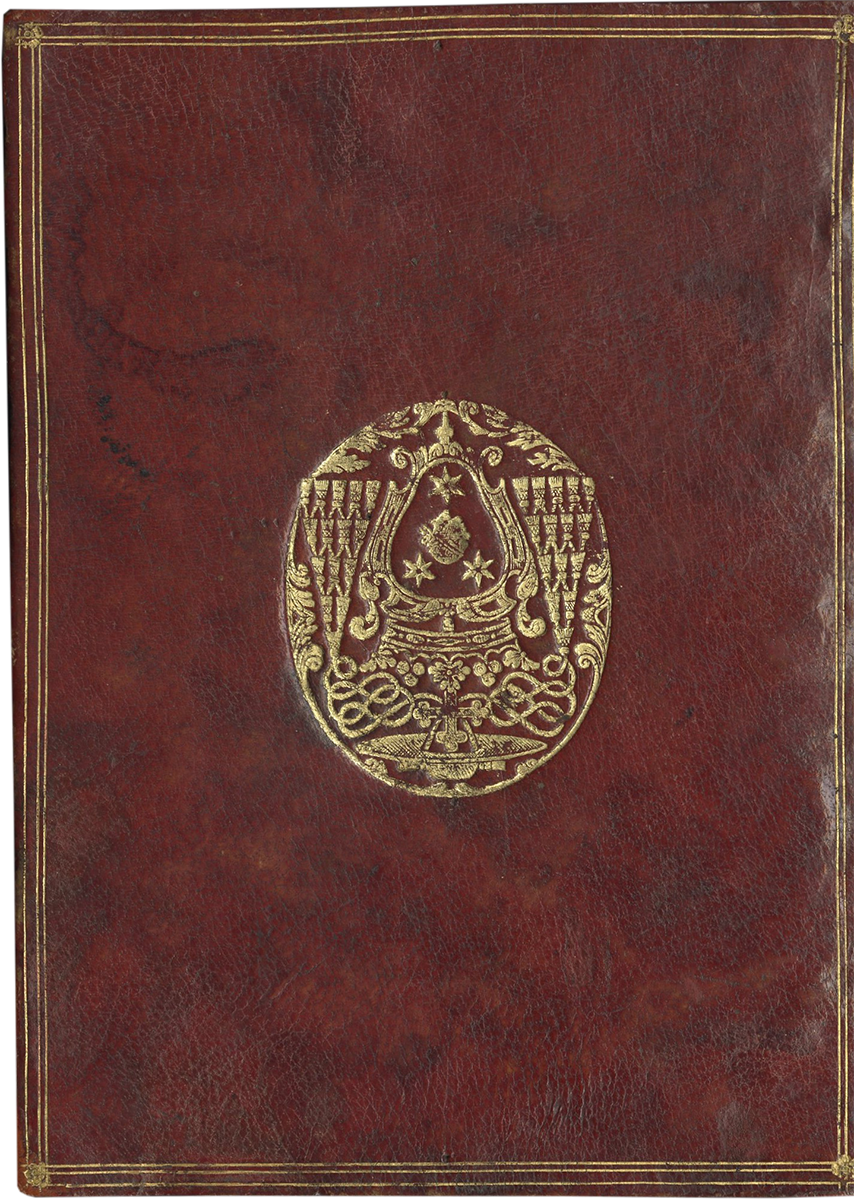

117 leaves, preceded by four paper flyleaves, and followed by one vellum and four paper ones; lacking 5 text leaves and two others possibly with miniatures or historiated initials, else apparently complete, collation 1 12, 2 8–1+1 (1st and 6th leaves missing, the 1st replaced with leaf that should follow f. 27), 38, 48–6 (1st leaf now bound as f. 13, 2nd and 6th leaves missing), 5–118, 126, 13–158, 16+2 (last 2 leaves canceled); ruled in pale red ink for 14 lines of text per page, justification c. 90 × 60 mm.; written in a regular formal gothic bookhand, with headings in red or blue, the calendar in red, blue, and gold, verse initial in gold on a pink and blue ground with white ornament, matching line-fillers, two-line initials in red and blue with white ornament, infilled with foliage, on a gold ground, attached to a foliate border running the height of the text in at least one margin, sometimes filling all four; borders in the fore-edge margin of every page, including those with no text, and also in the other margins of most pages, the borders of gold ivy leaves and black ink tendrils, interspersed with colored flowers, fruit, and occasional animals or birds; ELEVEN LARGE MINIATURES accompanied by full borders with small miniatures in the roundels and three-line initials; the vellum of high quality, generally clean and unblemished, a strip at the bottom of the last two leaves cut away and repaired with medieval vellum, the decoration slightly cropped in the top margins of some pages, occasional signs of use such as smudging, but generally in excellent condition. Bound in 18th-century red Morocco with gilt arms in the center of each cover, the impression deep and crisp but the gilding somewhat flaked, sewn on five cords, marbled endpapers, the edges of the leaves gilt, some extremely neat repairs to the joints and corners, but overall sound and in very good condition. Dimensions c. 165 × 120 mm.

Provenance

1. Written in Paris, for the local use (and with rubrics in blue, sometimes described as characteristic of Parisian production) certainly illuminated by the Master of the Munich Golden Legend during his earliest Parisian period and close to the Bedford Master.

2. Charles Le Goux de la Berchere (1647–1719), Archbishop of Narbonne (1703–1719), with his arms on both covers of the binding (see: Eugene Olivier, Manuel de l’amateur de reliures armoriées françaises, 33, 1932, pl. 2334, who states that he “possédait une des plus importantes bibliothèques de l’époque embrassant toutes les branches du savoir humain, qu’il légua aux Jésuites; une partie considérable de sa collection passa à son successeur sur le siège de Narbonne, Mgr de Beauveau”).

3. Renatus François de Beauvau du Rivau, Archbishop of Narbonne (1719–1739), signed along the gutter margin of f. 1 (as described Olivier, op. cit.); a large part of his collection has passed into the library at Toulouse.

4. A member of the Mosnier de Rochechinard family, of Dauphiné, with their small armorial bookplate (cf. Rietsrap, Armorial général, II, pl. CCLI; though the colors of the chief and the lion rampant are reversed, presumably simply an engraver’s error).

5. A member of the Angosse de Combères or Angosse d’Estornez families, with their larger armorial bookplate (cf. Rietstap, I, pl. LII).

6. J. R. Ritman (b. 1941–), Amsterdam, his sale, London Sotheby’s, A Second Selection of Illuminated Manuscripts from c. 1000 to c. 1522, The Property of J. R. Ritman, Sold for the Benefit of the Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica, Amsterdam, 19 June 2001, lot 15.

7. Private Collection.

Text

ff. 1–12v, Calendar, in French, with an entry for every day; major feasts in gold, the others alternately red or blue;

ff. 14–17v, Gospel Sequences, ending imperfect;

ff. 18–27v, Three prayers to the Virgin: the Obsecro te, beginning imperfect in the masculine form, the O intemerata, and the “Saluto te beatissima uirgo Maria, angelorum regina…”;

ff. 13r–v, 28–91, Hours of the Virgin, “... selon l’usage de Paris ...”, with nine lessons at Matins; the first leaf is bound before f. 14; f. 91v is ruled and has a three-sided border, but no text;

ff. 92–111, Seven Penitential Psalms, Litany, and two collects;

ff. 111v–114, Hours of the Cross;

ff. 115–117v, Hours of the Holy Spirit.

Illustration

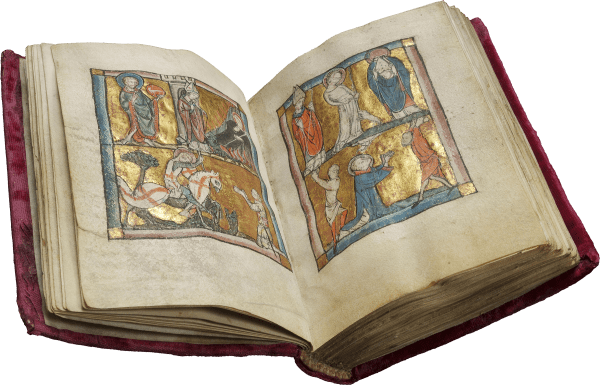

This ravishing manuscript was illuminated by The Master of the Munich Golden Legend, who is named after a manuscript in the Bavarian State Library in Munich (cgm 3) containing a French translation of Jacobus of Voragine’s Legenda aurea. The Master of the Munich Golden Legend, contributed to many of the great manuscripts that emerged out of the circle of the Bedford Master, including the Bedford Hours itself (British Library, Additional MS 18850) and the Sobieski Hours at Windsor Castle. He was tentatively identified by Eberhard König and more forcefully by Heribert Tenschert as Conrad of Toul, from an apparent signature in the illumination of the Munich volume (Das Pariser Stundenbuch an der Schwelle zum 15. Jahrhundert, 2011, pp. 139–48), although it must be admitted that no illuminator of that name is among the known records of the Parisian book trade. He was clearly a pupil or apprentice of the Bedford Master. In her catalogue of French manuscripts at the Walters Art Museum, which houses one of the star manuscripts by the artist (W.288), L.M.C. Randall suggests that some of the unusual iconography employed by the artist, especially in the border roundels (for example the scenes concerning Joachim and Anne, f. 13r), may have been inspired by a detail found in Jacobus’s accounts.

A partial study of the artist and his works has been published by Gregory Clark, Art in the Time of War (2016); a dissertation on him by Laurent Ungeheuer (2015) remains unpublished. He may have worked on panel paintings as well as being a manuscript illuminator, if Eleanor Spencer was correct in attributing to him the great panel depicting Jouvenal des Ursins and his family (Louvre, Inv. 9618), painted between 1445 and 1449 for their chapel in Notre Dame, Paris. The present manuscript was painted earlier than this, at about the time when Paris was occupied by English troops in the Hundred Years’ War, in 1420. After the occupation, and the outbreak of plague, many illuminators appear to have fled the city. It is not known whether the Master of the Munich Golden Legend left with them. Although he seems to have maintained a workshop in Paris, but there are also manuscripts made for use in Rouen to which he contributed, and another that suggests that he may have worked briefly in the vicinity of Angers or Le Mans (Plummer 1982, pp. 7–8).

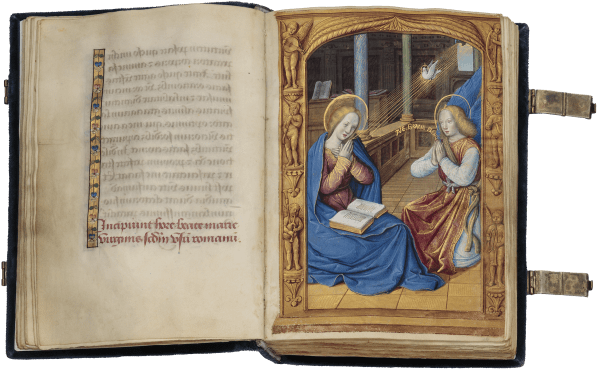

Slightly later and probably in Rouen he collaborated with the Dunois Master and with the Master of the Harvard Hannibal (e.g., in the Hours of Isabeau de Croix, Private Collection). We thank Gregory Clark for pointing out that the present manuscript, while still very much in the spirit of the finest works by the Bedford Master, compares closely also to the miniatures in the Isabeau de Croix Hours, especially the dazzling patterning in both books. Compare, for example, the particolored ceilings and wavy rays surrounding the doves of the Holy Spirit in splendor in the de Croix Pentecost (fig. 1) to the same subject in our Hours (fig. 2). Because of the presence of the Dunois Master in the de Croix Hours, Clark (2016, p. 271) dates that codex to around 1440. Yet, for Clark, several indicators in the present manuscript suggest an earlier date between about 1420 and 1430, notably, the composition of the Annunciation to the Shepherds, which closely mirrors a Boucicaut composition of about 1420 (Clark 2016, fig. 51). Likewise, the praying apostle pitched forward before an opened book in the Annunciation of our Hours reformulates two like figures in the foreground of the Pentecost in the Bedford Hours (fig. 3; London, British Library, Additional MS 18850, f. 132), tentatively dated between 1415 to 1425.

The depth and purity of the colors, and the brilliancy of the gold in this manuscript are dazzling. Roger Wieck’s description of “one of the most important and beautiful Books of Hours in the Walters Art Gallery” (fig. 4; W.288) may equally be applied to the present book, whose miniatures and, especially, marginal decoration closely mirror the Walters manuscript: “The manuscript was created during a period – the first third of the fifteenth century – and in a place – Paris – when manuscript illumination reached one of its effervescent climaxes. The miniatures are the work of one of the leading illuminators of the early fifteenth century, a painter christened the Master of the Munich Golden Legend.... Their fine quality, their deep and pure colors, their attention to detail, and their nearly perfect state of preservation make these miniatures remarkable. But they are even more so because of the rich array of events and scenes that the pictures unfold for us...” (Wieck, 1988, p. 11). Wieck illustrates all twelve of the miniatures as full-page color plates (pls. 1–12), allowing easy comparison with the present manuscript. Several of the border vignette scenes are found in both manuscripts, but the Walters manuscript has fewer medallions in the borders of the Annunciation and King David miniatures. The Walters volume has more medallions at the lesser hours but lacks the series of twenty-four calendar miniatures of the present book.

There are twenty-four miniatures in the lower borders of the calendar, depicting the Labors of the Months and the Signs of the Zodiac, in cusped quatrefoil frames, as follow

f. 1, Man warming himself by a fire, Aquarius;

f. 2, Man chopping trees, Pisces;

f. 3, Man pruning trees, Aries;

f. 4, Man carrying a branch, Taurus;

f. 5, Man on horseback with a falcon, Gemini;

f. 6, Man cutting grass with scythe, Cancer;

f. 7, Man reaping with sickle, Leo;

f. 8, Man threshing, Virgo;

f. 9, Man treading grapes, Libra;

f. 10, Man sowing seeds, Scorpio;

f. 11, Man knocking acorns from trees to feed pigs, Saggitarius;

f. 12, Man killing a pig, Capricorn.

The eleven large miniatures each have several border vignettes:

f. 13, The Annunciation; with seven border vignettes based on apocryphal writings or the Golden Legend, including: (i) Joachim and St. Anne offering lambs at the Temple, but being turned away; (ii) The Meeting of Joachim and Anne at the Golden Gate; (iii) The Nativity of the Virgin; (iv) St. Anne and the Virgin, each holding a book; (v) The Presentation of the Virgin at the Steps of the Temple; (vi) The Virgin at a loom; (vii) An angel.

Each of the following seven miniatures has five border vignettes, each with one or more angels praising, singing, or playing musical instruments:

f. 47, The Visitation;

f. 58v, The Nativity, with the Virgin adoring the Child, and Joseph warming a piece of cloth by a fire;

f. 64v, The Annunciation to the Shepherds;

f. 69v, The Adoration of the Magi;

f. 74r, The Presentation in the Temple;

f. 78v, The Flight into Egypt;

f. 86, The Coronation of the Virgin;

f. 92, King David in Penitence, in a landscape; with five border vignettes: (i) David beheading Goliath; (ii)Bathsheba bathing; (iii) King David telling Bathsheba's husband, Uriah the Hittite, to go into battle; (iv) Uriah saying his farewell to Bathsheba; (v) Uriah riding to his death.

f. 111 v, The Crucifixion, with John and the Virgin to the left of the Cross, Longinus and other soldiers to the right; with five border vignettes each with an angel holding the Instruments of the Passion;

f. 115, Pentecost, with the Virgin in the center, and St. Peter reading from an open book on the floor in the foreground; with five border vignettes, each with an angel playing a musical instrument.

We thank Gregory Clark for his expertise.

Literature

Published:

Gregory Clark, The Master of Morgan 453 and Manuscript Illumination in Paris during the English Occupation (1419–1435), Art in the Time of War. Text Image Context. Studies in Medieval Manuscript Illumination, 3, Toronto, 2016, p. 381 (as c. 1420–1430).

Further references:

Laurent Ungeheuer, “La Maître de la Légende dorée de Munich: Un enlumineur parisien du milieu du XVe siècle, formation, production, influences and collaborations,” Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, École Practique des Hautes Études, 2015.

Laurent Ungeheuer, “The Munich Golden Legend Master, a Disciple of the Bedford Master: Collaborations and Independence of a Parisian Illuminator between 1420 and 1450,” Revue de l’Art 195 (2017), pp. 23–32.

Roger Wieck. Time Sanctified. The Book of Hours in Medieval Art and Life, New York, 1988.

John Plummer, The Last Flowering French Painting in Manuscripts, 1420–1530: from American Collections, New York, 1982.