Early Medieval finger-rings, or rings from the so-called Migration era, occupy a class by themselves. Distinctly different from those prevalent in Antiquity, they are also of great rarity most likely because they are products of a chaotic period characterized by invasion not cultural fluorescence.

Tribal cultures–the Goths, the Visigoths, the Lombards, the Franks, the Ostrogoths, the Huns, etc.–wore their wealth as they moved from place to place. The persistence of Roman techniques can be seen in the intricate filigree and granulation of their gold work; however as the importance of the stone grew, the prominence of the bezel increased so that the beautiful uncut stone projected high above the finger. Rings of the projecting bezel type are found among the Lombards, the Ostrogoths, and the Franks. Another type, the spiral ring (already a form favored by the Celts), adopted by the Anglo-Saxons recalls the interlace of contemporary illuminated manuscripts. There are braided, twisted, and coiled examples. A small group of Anglo-Saxon rings also preserve niello decoration on flat or articulated bezels depicting mythic beasts, spirals, and other motifs.

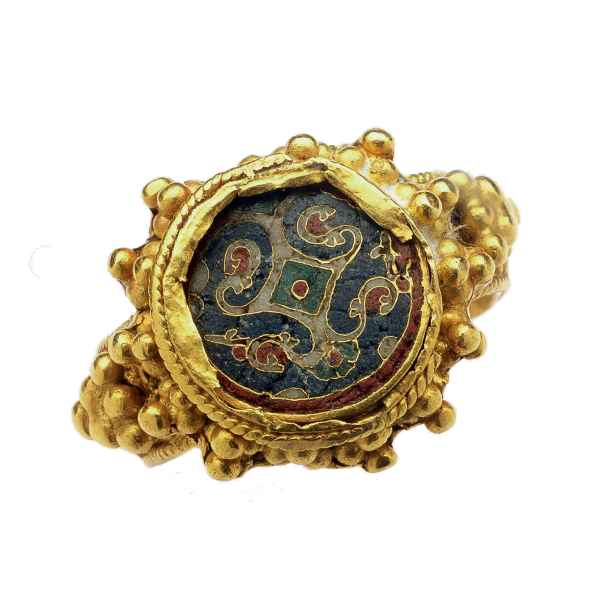

In Gaul, the Merovingians preferred a flat bezel on which designs could be engraved, whether they be portraits of the owner such as appears on the famous ring of the king Childerich or complex, difficult-to-decipher monograms, or animals. From the same historical milieu comes the intricate and imposing architectural ring, sometimes adorned with a cabochon garnet at the top of the bezel. The latter recalls on a minute scale Charlemagne's Palatine Chapel at Aachen with its rotunda form, arched galleries circling the central space, and dome. New types of byzantinizing forms, such as cloisonné work, came with the political stability of the Carolingian and Ottonian empires, and it is worth remembering that Otto II married a Byzantine princess.

Much of the evidence for the origins and the dating of Early Medieval Merovingian rings is archaeological. Rings decorated with shaved garnets, for example, come from sites that follow the route of the invasions of Attila the Hun (died 453) from Hungary to Gaul. Sometimes archaeological evidence suggests the gender of a wearer, as in the case of an architectural ring from the Guillou Collection buried in the tomb of a woman. Often, it provides important, independent means of dating, for hoards included dated coins, as well as other items made from precious metals.