Cover image: © 2025 Hannibal Books / Simon & Schuster. Used for review/commentary.

Books of Hours Books of Hope, Medieval Books of Hours and their Readers, ed. by Evelien Hauwaerts, with Emma De Nil & Caroline Van Cauwenberghe, Belgium, Hannibal Books, 2025

This remarkably original, highly readable book that accompanied an exhibition at the Bruges Public Library in 2025 will hopefully live on in print form for many years to come. Nine short essays by different contributors seek to answer questions commonly posed about Books of Hours: what do they contain, who made them, who read them, where and how did owners read them, what impact did reading the text have on a reader’s life. As the introduction states, it aims to provide a “nuanced picture of the children, men, and women who created, bought, read, and cherished Books of Hours.” For anyone who wants to learn more about the Book of Hours, from the general public to the specialized scholar, this book is a “must-read.”

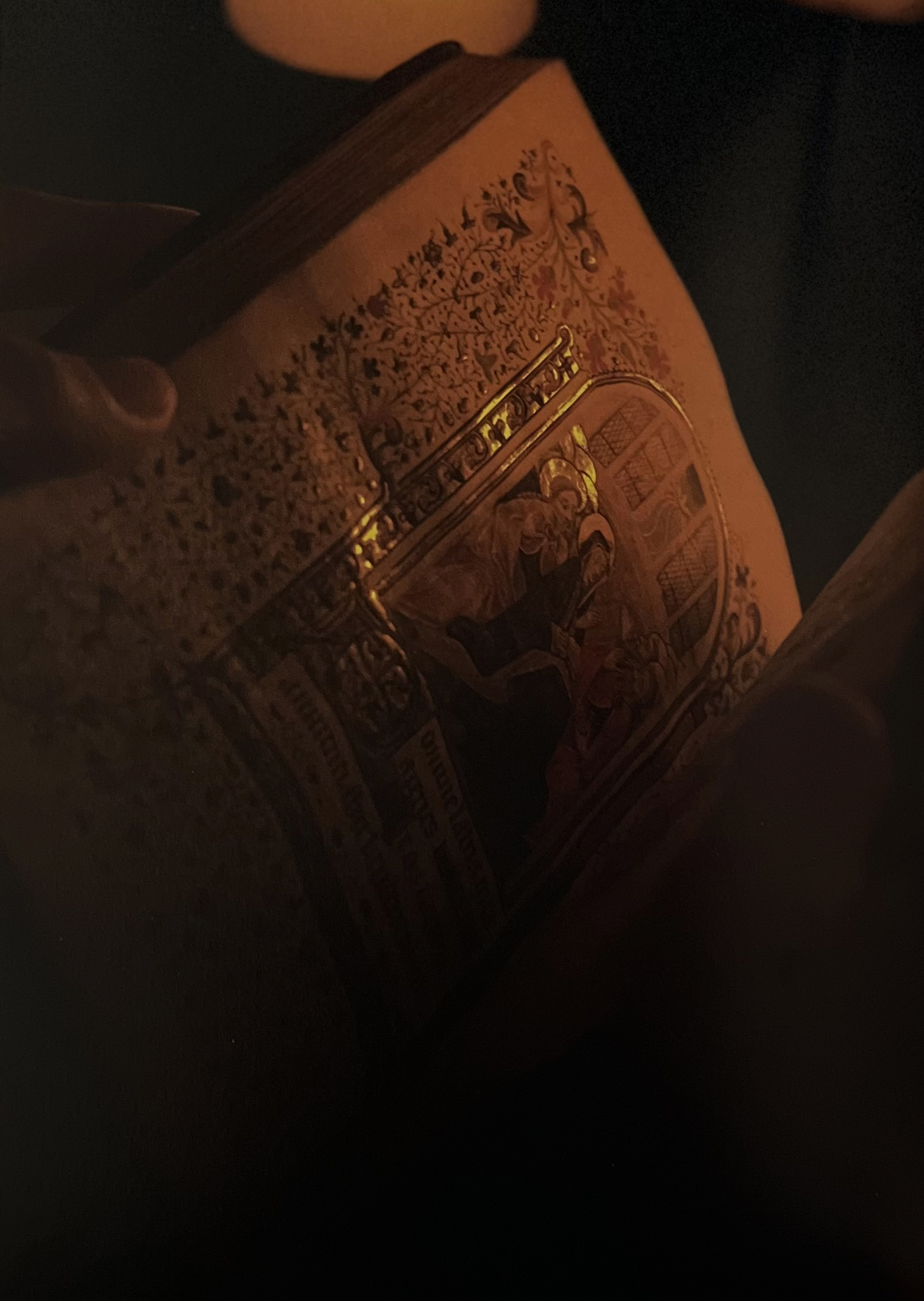

Attesting to the volume’s originality, the photographs that introduce each chapter immediately set the book apart from others of its genre. Each chapter starts with a detail of a Book of Hours held in the hands of a real-life person, and how different the hands are! Curator of Manuscripts at the Bruges Public Library and mastermind behind this project, Evelien Hauwaerts asked a local family to come into the library for the photography session. Young and old, male and female, different members of the family posed for the photos. Introducing chapter 1, a grown-up’s hands are heavily tattooed, whereas those of a young girl wearing nail polish appear before chapter 4, and a hefty man nestles a miniature book in his hands in chapter 7.

Photographs by Dominique Provost, from Books of Hours, Books of Hope,

© Openbare Bibliotheek Brugge

Hands holding books frequently reappear elsewhere too, in details of Netherland paintings, for example, in the frontispiece of the book. What could make clearer that these books were made to be read, to be used, to be handled and by different segments of the population.

Hans Memling, Triptych of John the Baptist (central panel, detail of Saint Barbara), 1479, oil on panel. Bruges, Musea Brugge, O.SJ0175.I.

It’s hard to choose what to highlight, since there are so many original ideas in this book. Chapter after chapter sets out to answer questions often asked about Books of Hours (and medieval manuscripts in general). Since they didn’t have electricity in the Middle Ages, wasn’t it difficult to see, especially in winter and at night? Chapter 8, “Reading after Dark,” focuses on the kinds of lighting that were available in the later Middle Ages, different candles, torches, tapers, lamps, candelabra, etc. And, because Evelien is so original and forward-thinking, what did she do: she had the photograph of the hands holding the book for this chapter shot in candlelight!

Photograph by Dominique Provost, from Books of Hours, Books of Hope,

© Openbare Bibliotheek Brugge

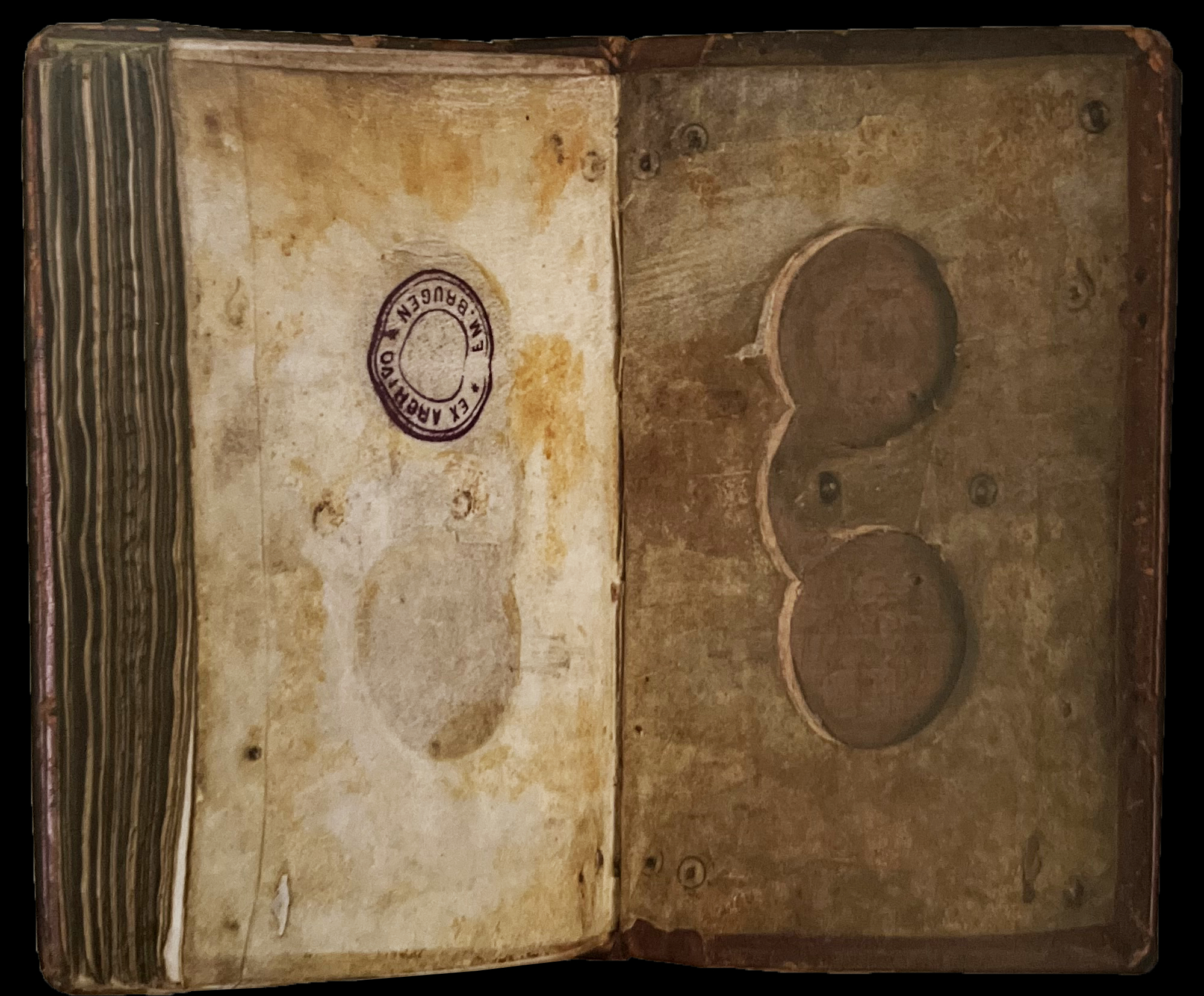

We see how differently the gold leaf and the pigments reflect in this setting. Another frequent question: because the images are so small and so detailed, did readers have trouble seeing all the minutiae? Chapter 7, “Reading Glasses in the Middle Ages,” clears up this point. It includes an illustration of a Book of Hours from the Bruges Public Library with a cut-out in its inside back cover to contain the owner’s glasses.

Cut-out for reading glasses, in the Book of Hours of Loys van Boghem, Lyon (?), 1526.

Bruges, Archives of the former Duinen Major Seminary, MS 66/35.

Elsewhere, the book considers questions about production and consumption by women as well as men (chapter 2, “Big Business,” and chapter 4, “Schooling and Literacy”), pointing out that entire families, men, women, and children, were often involved in production and that schooling for children of differing social and economic classes and both genders was more extensive than previously believed with the result that the ability to read was relatively widespread.

Chapter 5 on “Depictions of Devotional Books in Works of Art” approaches another question. Why are so many Books of Hours in such pristine condition? Looking at Netherlandish paintings and sculpture of the period in which owners appear with their Books of Hours,

Jan Provoost, Portrait of a Donor and Saint Nicholas and Portrait of a Donor and Saint Gudula (details), c. 1515–1521.

Bruges, Musea Brugge, 0000.GRO0216.I–0217.I.

this chapter grapples with the apparent contradiction between their pristine condition and the idea of their frequent use. Considering them as models of devotion signaling virtue, it points out that contemporary theologians urged their readers to regard text and image as platforms toward a higher state of being. It concludes that perhaps [readers] “used their Books of Hours by learning how not to use them at all.”

This last proposition is a little at odds with how eloquently most of the essays create a context for real people using their Books of Hours in their daily lives. A lot has been written on marginalia, but chapter 6, “Drolleries in the Margins of Holy Texts,” uses one mostly-unknown manuscript, the enchanting Psalter of Margaret II of Flanders (Bruges Public Library MS 820),

Psalter of Margaret II, Countess of Flanders. Bruges, Public Library, MS 820, Collection Flemish Community, f. 9r.

to suggest that the marginalia reflect Margaret’s everyday world, in which storytelling was an integral part of preacher’s tales she probably heard that found their way onto the manuscript page. Bringing the Book of Hours even closer to daily life is the last chapter (9, “Living the Hours”). An especially moving essay by Brother John Glasenapp recounts a horrifying car accident, from which he happily survived returning to the abbey to say the Divine Office. The very words of the prayers resonated with his lived experience. He continues to explore passages of the text of the Books of Hours, considering how they impacted their reader’s spiritual lives. I know of no other source on Books of Hours that attempts to resolve the affect that the reading of the text may have had on their readers.

Hoping that we hear more from Evelien Hauwaerts, for when I asked her what she wished she had included among the essays that she didn’t, I was similarly surprised by her original reflections. Without offering any spoilers here, I encourage readers to go to my Podcast with Evelien, where she shares more of her thought-provoking ideas about Books of Hours with listeners. You will never look at a Book of Hours in quite the same way again after reading this excellent book.

Sandra Hindman